Template:Infobox planet

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, after Mercury. Named after the Roman god of war, it is often referred to as the "Red Planet"[1][2] because the iron oxide prevalent on its surface gives it a reddish appearance.[3] Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin atmosphere, having surface features reminiscent both of the impact craters of the Moon and the valleys, deserts, and polar ice caps of Earth.

The rotational period and seasonal cycles of Mars are likewise similar to those of Earth, as is the tilt that produces the seasons. Mars is the site of Olympus Mons, the largest volcano and second-highest known mountain in the Solar System, and of Valles Marineris, one of the largest canyons in the Solar System. The smooth Borealis basin in the northern hemisphere covers 40% of the planet and may be a giant impact feature.[4][5] Mars has two moons, Phobos and Deimos, which are small and irregularly shaped. These may be captured asteroids,[6][7] similar to 5261 Eureka, a Mars trojan.

Until the first successful Mars flyby in 1965 by Mariner 4, many speculated about the presence of liquid water on the planet's surface. This was based on observed periodic variations in light and dark patches, particularly in the polar latitudes, which appeared to be seas and continents; long, dark striations were interpreted by some as irrigation channels for liquid water. These straight line features were later explained as optical illusions, though geological evidence gathered by uncrewed missions suggests that Mars once had large-scale water coverage on its surface at an earlier stage of its existence.[8] In 2005, radar data revealed the presence of large quantities of water ice at the poles[9] and at mid-latitudes.[10][11] The Mars rover Spirit sampled chemical compounds containing water molecules in March 2007. The Phoenix lander directly sampled water ice in shallow Martian soil on July 31, 2008.[12] On September 28, 2015, NASA announced the presence of briny flowing salt water on the Martian surface.[13]

Mars is host to seven functioning spacecraft: five in orbit—2001 Mars Odyssey, Mars Express, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, MAVEN and Mars Orbiter Mission—and two on the surface—Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity and the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity. Observations by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have revealed possible flowing water during the warmest months on Mars.[14] In 2013, NASA's Curiosity rover discovered that Mars's soil contains between 1.5% and 3% water by mass (albeit attached to other compounds and thus not freely accessible).[15]

There are ongoing investigations assessing the past habitability potential of Mars, as well as the possibility of extant life. In situ investigations have been performed by the Viking landers, Spirit and Opportunity rovers, Phoenix lander, and Curiosity rover. Future astrobiology missions are planned, including the Mars 2020 and ExoMars rovers.[16][17][18][19]

Mars can easily be seen from Earth with the naked eye, as can its reddish coloring. Its apparent magnitude reaches −2.91,[20] which is surpassed only by Jupiter, Venus, the Moon, and the Sun. Optical ground-based telescopes are typically limited to resolving features about 300 kilometers (

To convert an amount with miles, use the unit-code "mi" such as in: {{convert|4|mi|km}} → 4 miles (6.4 km). Template:J. Template:J for other unit-codes.

) across when Earth and Mars are closest because of Earth's atmosphere.[21]

Physical characteristics[]

Mars is approximately half the diameter of Earth, and its surface area is only slightly less than the total area of Earth's dry land.[20] Mars is less dense than Earth, having about 15% of Earth's volume and 11% of Earth's mass, resulting in about 38% of Earth's surface gravity. The red-orange appearance of the Martian surface is caused by iron(III) oxide, or rust.[22] It can look like butterscotch,[23] and other common surface colors include golden, brown, tan, and greenish, depending on the minerals present.[23] Template:Multiple image

Internal structure[]

Like Earth, Mars has differentiated into a dense metallic core overlaid by less dense materials.[24] Current models of its interior imply a core region about Template:Convert/±/AoffSoff (Template:Convert/±/AonSoff) in radius, consisting primarily of iron and nickel with about 16–17% sulfur.[25] This iron(II) sulfide core is thought to be twice as rich in lighter elements than Earth's core.[26] The core is surrounded by a silicate mantle that formed many of the tectonic and volcanic features on the planet, but it appears to be dormant. Besides silicon and oxygen, the most abundant elements in the Martian crust are iron, magnesium, aluminum, calcium, and potassium. The average thickness of the planet's crust is about 50 km (Template:Convert/round mi), with a maximum thickness of 125 km (Template:Convert/round mi).[26] Earth's crust, averaging 40 km (Template:Convert/round mi), is only one third as thick as Mars', in ratio to the sizes of the two planets.

Surface geology[]

- Main article: Geology of Mars

Mars is a terrestrial planet that consists of minerals containing silicon and oxygen, metals, and other elements that typically make up rock. The surface of Mars is primarily composed of tholeiitic basalt,[27] although parts are more silica-rich than typical basalt and may be similar to andesitic rocks on Earth or silica glass. Regions of low albedo show concentrations of plagioclase feldspar, with northern low albedo regions displaying higher than normal concentrations of sheet silicates and high-silicon glass. Parts of the southern highlands include detectable amounts of high-calcium pyroxenes. Localized concentrations of hematite and olivine have been found.[28] Much of the surface is deeply covered by finely grained iron(III) oxide dust.[29][30]

Geologic map of Mars (USGS, 2014)[31]

Although Mars has no evidence of a structured global magnetic field,[32] observations show that parts of the planet's crust have been magnetized, and that alternating polarity reversals of its dipole field have occurred in the past. This paleomagnetism of magnetically susceptible minerals has properties that are similar to the alternating bands found on the ocean floors of Earth. One theory, published in 1999 and re-examined in October 2005 (with the help of the Mars Global Surveyor), is that these bands demonstrate plate tectonics on Mars four billion years ago, before the planetary dynamo ceased to function and the planet's magnetic field faded away.[33]

During the Solar System's formation, Mars was created as the result of a stochastic process of run-away accretion out of the protoplanetary disk that orbited the Sun. Mars has many distinctive chemical features caused by its position in the Solar System. Elements with comparatively low boiling points, such as chlorine, phosphorus, and sulphur, are much more common on Mars than Earth; these elements were probably removed from areas closer to the Sun by the young star's energetic solar wind.[34]

After the formation of the planets, all were subjected to the so-called "Late Heavy Bombardment". About 60% of the surface of Mars shows a record of impacts from that era,[35][36][37] whereas much of the remaining surface is probably underlain by immense impact basins caused by those events. There is evidence of an enormous impact basin in the northern hemisphere of Mars, spanning 10,600 by 8,500 km (Template:Convert/round by Template:Convert/round mi), or roughly four times larger than the Moon's South Pole – Aitken basin, the largest impact basin yet discovered.[4][5] This theory suggests that Mars was struck by a Pluto-sized body about four billion years ago. The event, thought to be the cause of the Martian hemispheric dichotomy, created the smooth Borealis basin that covers 40% of the planet.[38][39]

Artist's impression of how Mars may have looked four billion years ago[40]

The geological history of Mars can be split into many periods, but the following are the three primary periods:[41][42]

- Noachian period (named after Noachis Terra): Formation of the oldest extant surfaces of Mars, 4.5 billion years ago to 3.5 billion years ago. Noachian age surfaces are scarred by many large impact craters. The Tharsis bulge, a volcanic upland, is thought to have formed during this period, with extensive flooding by liquid water late in the period.

- Hesperian period (named after Hesperia Planum): 3.5 billion years ago to 2.9–3.3 billion years ago. The Hesperian period is marked by the formation of extensive lava plains.

- Amazonian period (named after Amazonis Planitia): 2.9–3.3 billion years ago to present. Amazonian regions have few meteorite impact craters, but are otherwise quite varied. Olympus Mons formed during this period, along with lava flows elsewhere on Mars.

Geological activity is still taking place on Mars. The Athabasca Valles is home to sheet-like lava flows up to about 200 Mya. Water flows in the grabens called the Cerberus Fossae occurred less than 20 Mya, indicating equally recent volcanic intrusions.[43] On February 19, 2008, images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter showed evidence of an avalanche from a 700 m high cliff.[44]

Soil[]

- Main article: Martian soil

Exposure of silica-rich dust uncovered by the Spirit rover

The Phoenix lander returned data showing Martian soil to be slightly alkaline and containing elements such as magnesium, sodium, potassium and chlorine. These nutrients are found in gardens on Earth, and they are necessary for growth of plants.[45] Experiments performed by the lander showed that the Martian soil has a basic pH of 7.7, and contains 0.6% of the salt perchlorate.[46][47][48][49]

Streaks are common across Mars and new ones appear frequently on steep slopes of craters, troughs, and valleys. The streaks are dark at first and get lighter with age. The streaks can start in a tiny area which then spread out for hundreds of metres. They have been seen to follow the edges of boulders and other obstacles in their path. The commonly accepted theories include that they are dark underlying layers of soil revealed after avalanches of bright dust or dust devils.[50] Several explanations have been put forward, including those that involve water or even the growth of organisms.[51][52]

Hydrology[]

- Main article: Water on Mars

Liquid water cannot exist on the surface of Mars due to low atmospheric pressure, which is about 100 times thinner than Earth's,[53] except at the lowest elevations for short periods.[54][55] The two polar ice caps appear to be made largely of water.[56][57] The volume of water ice in the south polar ice cap, if melted, would be sufficient to cover the entire planetary surface to a depth of 11 meters (Template:Convert/round ft).[58] A permafrost mantle stretches from the pole to latitudes of about 60°.[56] Large quantities of water ice are thought to be trapped within the thick cryosphere of Mars. Radar data from Mars Express and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter show large quantities of water ice both at the poles (July 2005)[9][59] and at middle latitudes (November 2008).[10] The Phoenix lander directly sampled water ice in shallow Martian soil on July 31, 2008.[12]

Photomicrograph by Opportunity showing a gray hematite concretion, nicknamed "blueberries", indicative of the past presence of liquid water

Landforms visible on Mars strongly suggest that liquid water has existed on the planet's surface. Huge linear swathes of scoured ground, known as outflow channels, cut across the surface in around 25 places. These are thought to record erosion which occurred during the catastrophic release of water from subsurface aquifers, though some of these structures have been hypothesized to result from the action of glaciers or lava.[60][61] One of the larger examples, Ma'adim Vallis is 700 km (Template:Convert/round mi) long and much bigger than the Grand Canyon with a width of 20 km (Template:Convert/round mi) and a depth of 2 km (Template:Convert/round mi) in places. It is thought to have been carved by flowing water early in Mars's history.[62] The youngest of these channels are thought to have formed as recently as only a few million years ago.[63] Elsewhere, particularly on the oldest areas of the Martian surface, finer-scale, dendritic networks of valleys are spread across significant proportions of the landscape. Features of these valleys and their distribution strongly imply that they were carved by runoff resulting from rain or snow fall in early Mars history. Subsurface water flow and groundwater sapping may play important subsidiary roles in some networks, but precipitation was probably the root cause of the incision in almost all cases.[64]

Along crater and canyon walls, there are thousands of features that appear similar to terrestrial gullies. The gullies tend to be in the highlands of the southern hemisphere and to face the Equator; all are poleward of 30° latitude. A number of authors have suggested that their formation process involves liquid water, probably from melting ice,[65][66] although others have argued for formation mechanisms involving carbon dioxide frost or the movement of dry dust.[67][68] No partially degraded gullies have formed by weathering and no superimposed impact craters have been observed, indicating that these are young features, possibly still active.[66] Other geological features, such as deltas and alluvial fans preserved in craters, are further evidence for warmer, wetter conditions at an interval or intervals in earlier Mars history.[69] Such conditions necessarily require the widespread presence of crater lakes across a large proportion of the surface, for which there is independent mineralogical, sedimentological and geomorphological evidence.[70]

Composition of "Yellowknife Bay" rocks. Rock veins are higher in calcium and sulfur than "portage" soil (Curiosity, APXS, 2013).

Further evidence that liquid water once existed on the surface of Mars comes from the detection of specific minerals such as hematite and goethite, both of which sometimes form in the presence of water.[71] In 2004, Opportunity detected the mineral jarosite. This forms only in the presence of acidic water, which demonstrates that water once existed on Mars.[72] More recent evidence for liquid water comes from the finding of the mineral gypsum on the surface by NASA's Mars rover Opportunity in December 2011.[73][74] The study leader Francis McCubbin, a planetary scientist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque looking at hydroxals in crystalline minerals from Mars, states that the amount of water in the upper mantle of Mars is equal to or greater than that of Earth at 50–300 parts per million of water, which is enough to cover the entire planet to a depth of −−1,200 m (Template:Convert/round ft).[75]

On March 18, 2013, NASA reported evidence from instruments on the Curiosity rover of mineral hydration, likely hydrated calcium sulfate, in several rock samples including the broken fragments of "Tintina" rock and "Sutton Inlier" rock as well as in veins and nodules in other rocks like "Knorr" rock and "Wernicke" rock.[76][77][78] Analysis using the rover's DAN instrument provided evidence of subsurface water, amounting to as much as 4% water content, down to a depth of 60 cm (Template:Convert/round in), in the rover's traverse from the Bradbury Landing site to the Yellowknife Bay area in the Glenelg terrain.[76] On September 28, 2015, NASA announced that they had found conclusive evidence of hydrated brine flows on recurring slope lineae, based on spectrometer readings of the darkened areas of slopes.[79][80][81] These observations provided confirmation of earlier hypotheses based on timing of formation and rate of growth that these dark streaks resulted from water flowing in the very shallow subsurface.[82] The streaks contain hydrated salts, perchlorates, which have water molecules in their crystal structure.[83] The streaks flow downhill in Martian summer, when the temperature is above –23 degrees Celsius, and freeze at lower temperatures.[84]

Researchers think that much of the low northern plains of the planet were covered with an ocean hundreds of meters deep, though this remains controversial.[85] In March 2015, scientists stated that such an ocean might have been the size of Earth's Arctic Ocean. This finding was derived from the ratio of water and deuterium in the modern Martian atmosphere compared to the ratio found on Earth. Eight times as much deuterium was found at Mars than exists on Earth, suggesting that ancient Mars had significantly higher levels of water. Results from the Curiosity rover had previously found a high ratio of deuterium in Gale Crater, though not significantly high enough to suggest the presence of an ocean. Other scientists caution that this new study has not been confirmed, and point out that Martian climate models have not yet shown that the planet was warm enough in the past to support bodies of liquid water.[86]

Polar caps[]

- Main article: Martian polar ice caps

Template:Multiple image Mars has two permanent polar ice caps. During a pole's winter, it lies in continuous darkness, chilling the surface and causing the deposition of 25–30% of the atmosphere into slabs of CO2 ice (dry ice).[87] When the poles are again exposed to sunlight, the frozen CO2 sublimes, creating enormous winds that sweep off the poles as fast as 400 km/h (Template:Convert/round mph). These seasonal actions transport large amounts of dust and water vapor, giving rise to Earth-like frost and large cirrus clouds. Clouds of water-ice were photographed by the Opportunity rover in 2004.[88]

The polar caps at both poles consist primarily (70%) of water ice. Frozen carbon dioxide accumulates as a comparatively thin layer about one metre thick on the north cap in the northern winter only, whereas the south cap has a permanent dry ice cover about eight metres thick. This permanent dry ice cover at the south pole is peppered by flat floored, shallow, roughly circular pits, which repeat imaging shows are expanding by meters per year; this suggests that the permanent CO2 cover over the south pole water ice is degrading over time.[89] The northern polar cap has a diameter of about 1,000 km (Template:Convert/round mi) during the northern Mars summer,[90] and contains about Template:Convert/e6km3 of ice, which, if spread evenly on the cap, would be 2 km (Template:Convert/round mi) thick.[91] (This compares to a volume of Template:Convert/e6km3 for the Greenland ice sheet.) The southern polar cap has a diameter of 350 km (Template:Convert/round mi) and a thickness of 3 km (Template:Convert/round mi).[92] The total volume of ice in the south polar cap plus the adjacent layered deposits has been estimated at 1.6 million cubic km.[93] Both polar caps show spiral troughs, which recent analysis of SHARAD ice penetrating radar has shown are a result of katabatic winds that spiral due to the Coriolis Effect.[94][95]

The seasonal frosting of areas near the southern ice cap results in the formation of transparent 1-metre-thick slabs of dry ice above the ground. With the arrival of spring, sunlight warms the subsurface and pressure from subliming CO2 builds up under a slab, elevating and ultimately rupturing it. This leads to geyser-like eruptions of CO2 gas mixed with dark basaltic sand or dust. This process is rapid, observed happening in the space of a few days, weeks or months, a rate of change rather unusual in geology – especially for Mars. The gas rushing underneath a slab to the site of a geyser carves a spiderweb-like pattern of radial channels under the ice, the process being the inverted equivalent of an erosion network formed by water draining through a single plughole.[96][97][98][99]

Geography and naming of surface features[]

- Main article: Geography of Mars

A MOLA-based topographic map showing highlands (red and orange) dominating the southern hemisphere of Mars, lowlands (blue) the northern. Volcanic plateaus delimit regions of the northern plains, whereas the highlands are punctuated by several large impact basins.

Although better remembered for mapping the Moon, Johann Heinrich Mädler and Wilhelm Beer were the first "areographers". They began by establishing that most of Mars's surface features were permanent and by more precisely determining the planet's rotation period. In 1840, Mädler combined ten years of observations and drew the first map of Mars. Rather than giving names to the various markings, Beer and Mädler simply designated them with letters; Meridian Bay (Sinus Meridiani) was thus feature "a".[100]

Today, features on Mars are named from a variety of sources. Albedo features are named for classical mythology. Craters larger than 60 km are named for deceased scientists and writers and others who have contributed to the study of Mars. Craters smaller than 60 km are named for towns and villages of the world with populations of less than 100,000. Large valleys are named for the word "Mars" or "star" in various languages; small valleys are named for rivers.[101]

Large albedo features retain many of the older names, but are often updated to reflect new knowledge of the nature of the features. For example, Nix Olympica (the snows of Olympus) has become Olympus Mons (Mount Olympus).[102] The surface of Mars as seen from Earth is divided into two kinds of areas, with differing albedo. The paler plains covered with dust and sand rich in reddish iron oxides were once thought of as Martian "continents" and given names like Arabia Terra (land of Arabia) or Amazonis Planitia (Amazonian plain). The dark features were thought to be seas, hence their names Mare Erythraeum, Mare Sirenum and Aurorae Sinus. The largest dark feature seen from Earth is Syrtis Major Planum.[103] The permanent northern polar ice cap is named Planum Boreum, whereas the southern cap is called Planum Australe.

Mars's equator is defined by its rotation, but the location of its Prime Meridian was specified, as was Earth's (at Greenwich), by choice of an arbitrary point; Mädler and Beer selected a line in 1830 for their first maps of Mars. After the spacecraft Mariner 9 provided extensive imagery of Mars in 1972, a small crater (later called Airy-0), located in the Sinus Meridiani ("Middle Bay" or "Meridian Bay"), was chosen for the definition of 0.0° longitude to coincide with the original selection.[104]

Because Mars has no oceans and hence no "sea level", a zero-elevation surface had to be selected as a reference level; this is called the areoid[105] of Mars, analogous to the terrestrial geoid. Zero altitude was defined by the height at which there is 610.5 Pa (Template:Convert/round mbar) of atmospheric pressure.[106] This pressure corresponds to the triple point of water, and it is about 0.6% of the sea level surface pressure on Earth (0.006 atm).[107] In practice, today this surface is defined directly from satellite gravity measurements.

Map of quadrangles[]

For mapping purposes, the United States Geological Survey divides the surface of Mars into thirty "quadrangles", each named for a prominent physiographic feature within that quadrangle.[108][109] The quadrangles can be seen and explored via the interactive image map below.

Template:Mars Quads - By Name

Impact topography[]

Bonneville crater and Spirit rover's lander

The dichotomy of Martian topography is striking: northern plains flattened by lava flows contrast with the southern highlands, pitted and cratered by ancient impacts. Research in 2008 has presented evidence regarding a theory proposed in 1980 postulating that, four billion years ago, the northern hemisphere of Mars was struck by an object one-tenth to two-thirds the size of Earth's Moon. If validated, this would make the northern hemisphere of Mars the site of an impact crater 10,600 by 8,500 km (Template:Convert/round by Template:Convert/round mi) in size, or roughly the area of Europe, Asia, and Australia combined, surpassing the South Pole–Aitken basin as the largest impact crater in the Solar System.[4][5]

Fresh asteroid impact on Mars at Template:Coord – before/March 27 & after/March 28, 2012 (MRO)[110]

Mars is scarred by a number of impact craters: a total of 43,000 craters with a diameter of 5 km (Template:Convert/round mi) or greater have been found.[111] The largest confirmed of these is the Hellas impact basin, a light albedo feature clearly visible from Earth.[112] Due to the smaller mass of Mars, the probability of an object colliding with the planet is about half that of Earth. Mars is located closer to the asteroid belt, so it has an increased chance of being struck by materials from that source. Mars is more likely to be struck by short-period comets, i.e., those that lie within the orbit of Jupiter.[113] In spite of this, there are far fewer craters on Mars compared with the Moon, because the atmosphere of Mars provides protection against small meteors. Craters can have a morphology that suggests the ground became wet after the meteor impacted.[114]

Volcanoes[]

Viking 1 image of Olympus Mons. The volcano and related terrain are approximately 550 km (Template:Convert/round mi) across.

- Main article: Volcanology of Mars

The shield volcano Olympus Mons (Mount Olympus) is an extinct volcano in the vast upland region Tharsis, which contains several other large volcanoes. Olympus Mons is roughly three times the height of Mount Everest, which in comparison stands at just over 8.8 km (Template:Convert/round mi).[115] It is either the tallest or second-tallest mountain in the Solar System, depending on how it is measured, with various sources giving figures ranging from about 21 to 27 km (Template:Convert/round to Template:Convert/round mi) high.[116][117]

Tectonic sites[]

Valles Marineris (2001 Mars Odyssey)

The large canyon, Valles Marineris (Latin for Mariner Valleys, also known as Agathadaemon in the old canal maps), has a length of 4,000 km (Template:Convert/round mi) and a depth of up to 7 km (Template:Convert/round mi). The length of Valles Marineris is equivalent to the length of Europe and extends across one-fifth the circumference of Mars. By comparison, the Grand Canyon on Earth is only 446 km (Template:Convert/round mi) long and nearly 2 km (Template:Convert/round mi) deep. Valles Marineris was formed due to the swelling of the Tharsis area which caused the crust in the area of Valles Marineris to collapse. In 2012, it was proposed that Valles Marineris is not just a graben, but a plate boundary where 150 km (Template:Convert/round mi) of transverse motion has occurred, making Mars a planet with possibly a two-plate tectonic arrangement.[118][119]

Holes[]

Images from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) aboard NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter have revealed seven possible cave entrances on the flanks of the volcano Arsia Mons.[120] The caves, named after loved ones of their discoverers, are collectively known as the "seven sisters".[121] Cave entrances measure from 100 to 252 m (Template:Convert/round to Template:Convert/round ft) wide and they are estimated to be at least 73 to 96 m (Template:Convert/round to Template:Convert/round ft) deep. Because light does not reach the floor of most of the caves, it is possible that they extend much deeper than these lower estimates and widen below the surface. "Dena" is the only exception; its floor is visible and was measured to be 130 m (Template:Convert/round ft) deep. The interiors of these caverns may be protected from micrometeoroids, UV radiation, solar flares and high energy particles that bombard the planet's surface.[122]

Atmosphere[]

- Main article: Atmosphere of Mars

Mars lost its magnetosphere 4 billion years ago,[124] possibly because of numerous asteroid strikes,[125] so the solar wind interacts directly with the Martian ionosphere, lowering the atmospheric density by stripping away atoms from the outer layer. Both Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Express have detected ionised atmospheric particles trailing off into space behind Mars,[124][126] and this atmospheric loss is being studied by the MAVEN orbiter. Compared to Earth, the atmosphere of Mars is quite rarefied. Atmospheric pressure on the surface today ranges from a low of 30 Pa (Template:Convert/round kPa) on Olympus Mons to over 1,155 Pa (Template:Convert/round kPa) in Hellas Planitia, with a mean pressure at the surface level of 600 Pa (Template:Convert/round kPa).[127] The highest atmospheric density on Mars is equal to that found 35 km (Template:Convert/round mi)[128] above Earth's surface. The resulting mean surface pressure is only 0.6% of that of Earth (101.3 kPa). The scale height of the atmosphere is about 10.8 km (Template:Convert/round mi),[129] which is higher than Earth's (6 km (Template:Convert/round mi)) because the surface gravity of Mars is only about 38% of Earth's, an effect offset by both the lower temperature and 50% higher average molecular weight of the atmosphere of Mars.

The tenuous atmosphere of Mars visible on the horizon

The atmosphere of Mars consists of about 96% carbon dioxide, 1.93% argon and 1.89% nitrogen along with traces of oxygen and water.[20][130] The atmosphere is quite dusty, containing particulates about 1.5 µm in diameter which give the Martian sky a tawny color when seen from the surface.[131] It may take on a pink hue due to iron oxide particles suspended in it.[2]

Methane has been detected in the Martian atmosphere with a mole fraction of about 30 ppb;[132][133] it occurs in extended plumes, and the profiles imply that the methane was released from discrete regions. In northern midsummer, the principal plume contained 19,000 metric tons of methane, with an estimated source strength of 0.6 kilograms per second.[134][135] The profiles suggest that there may be two local source regions, the first centered near Template:Coord and the second near Template:Coord.[134] It is estimated that Mars must produce 270 tonnes per year of methane.[134][136]

Methane can exist in the Martian atmosphere for only a limited period before it is destroyed—estimates of its lifetime range from 0.6–4 years.[134][137] Its presence despite this short lifetime indicates that an active source of the gas must be present. Volcanic activity, cometary impacts, and the presence of methanogenic microbial life forms are among possible sources. Methane could be produced by a non-biological process called serpentinizationTemplate:Efn involving water, carbon dioxide, and the mineral olivine, which is known to be common on Mars.[138]

Potential sources and sinks of methane (Template:Chem2) on Mars

The Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars in August 2012, is able to make measurements that distinguish between different isotopologues of methane,[139] but even if the mission is to determine that microscopic Martian life is the source of the methane, the life forms likely reside far below the surface, outside of the rover's reach.[140] The first measurements with the Tunable Laser Spectrometer (TLS) indicated that there is less than 5 ppb of methane at the landing site at the point of the measurement.[141][142][143][144] On September 19, 2013, NASA scientists, from further measurements by Curiosity, reported no detection of atmospheric methane with a measured value of Template:Val ppbv corresponding to an upper limit of only 1.3 ppbv (95% confidence limit) and, as a result, conclude that the probability of current methanogenic microbial activity on Mars is reduced.[145][146][147]

The Mars Orbiter Mission by India is searching for methane in the atmosphere,[148] while the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, planned to launch in 2016, would further study the methane as well as its decomposition products, such as formaldehyde and methanol.[149]

On December 16, 2014, NASA reported the Curiosity rover detected a "tenfold spike", likely localized, in the amount of methane in the Martian atmosphere. Sample measurements taken "a dozen times over 20 months" showed increases in late 2013 and early 2014, averaging "7 parts of methane per billion in the atmosphere." Before and after that, readings averaged around one-tenth that level.[150][151]

Ammonia was tentatively detected on Mars by the Mars Express satellite, but with its relatively short lifetime, it is not clear what produced it.[152] Ammonia is not stable in the Martian atmosphere and breaks down after a few hours. One possible source is volcanic activity.[152]

Aurora[]

In 1994 the European Space Agency's Mars Express found an ultraviolet glow coming from "magnetic umbrellas" in the southern hemisphere. Mars does not have a global magnetic field which guides charged particles entering the atmosphere. Mars has multiple umbrella-shaped magnetic fields mainly in the southern hemisphere, which are remnants of a global field that decayed billions of years ago.

In late December 2014, NASA's MAVEN spacecraft detected evidence of widespread auroras in Mars's northern hemisphere and descended to approximately 20–30 degrees North latitude of Mars's equator. The particles causing the aurora penetrated into the Martian atmosphere, creating auroras below 100 km above the surface, Earth's auroras range from 100 km to 500 km above the surface. Magnetic fields in the solar wind drape over Mars, into the atmosphere, and the charged particles follow the solar wind magnetic field lines into the atmosphere, causing auroras to occur outside the magnetic umbrellas.[153]

On March 18, 2015, NASA reported the detection of an aurora that is not fully understood and an unexplained dust cloud in the atmosphere of Mars.[154]

Climate[]

- Main article: Climate of Mars

Template:Multiple image

Of all the planets in the Solar System, the seasons of Mars are the most Earth-like, due to the similar tilts of the two planets' rotational axes. The lengths of the Martian seasons are about twice those of Earth's because Mars's greater distance from the Sun leads to the Martian year being about two Earth years long. Martian surface temperatures vary from lows of about −143 °C (Template:Convert/roundT1 °F) at the winter polar caps[155] to highs of up to 35 °C (Template:Convert/roundT0 °F) in equatorial summer.[156] The wide range in temperatures is due to the thin atmosphere which cannot store much solar heat, the low atmospheric pressure, and the low thermal inertia of Martian soil.[157] The planet is 1.52 times as far from the Sun as Earth, resulting in just 43% of the amount of sunlight.[158]

If Mars had an Earth-like orbit, its seasons would be similar to Earth's because its axial tilt is similar to Earth's. The comparatively large eccentricity of the Martian orbit has a significant effect. Mars is near perihelion when it is summer in the southern hemisphere and winter in the north, and near aphelion when it is winter in the southern hemisphere and summer in the north. As a result, the seasons in the southern hemisphere are more extreme and the seasons in the northern are milder than would otherwise be the case. The summer temperatures in the south can be up to 30 K (Template:Convert/C-change F-change) warmer than the equivalent summer temperatures in the north.[159]

Mars has the largest dust storms in the Solar System. These can vary from a storm over a small area, to gigantic storms that cover the entire planet. They tend to occur when Mars is closest to the Sun, and have been shown to increase the global temperature.[160]

Orbit and rotation[]

- Main article: Orbit of Mars

Mars is about 143,000,000 miles (Template:Scinote/e km) from the Sun; its orbital period is 687 (Earth) days, depicted in red. Earth's orbit is in blue.

Mars's average distance from the Sun is roughly 143,000,000 miles (Template:Scinote/e km), and its orbital period is 687 (Earth) days. The solar day (or sol) on Mars is only slightly longer than an Earth day: 24 hours, 39 minutes, and 35.244 seconds.[161] A Martian year is equal to 1.8809 Earth years, or 1 year, 320 days, and 18.2 hours.[20]

The axial tilt of Mars is 25.19 degrees relative to its orbital plane, which is similar to the axial tilt of Earth.[20] As a result, Mars has seasons like Earth, though on Mars, they are nearly twice as long because its orbital period is that much longer. In the present day epoch, the orientation of the north pole of Mars is close to the star Deneb.[162] Mars passed an aphelion in March 2010[163] and its perihelion in March 2011.[164] The next aphelion came in February 2012[164] and the next perihelion came in January 2013.[164]

Mars has a relatively pronounced orbital eccentricity of about 0.09; of the seven other planets in the Solar System, only Mercury has a larger orbital eccentricity. It is known that in the past, Mars has had a much more circular orbit. At one point, 1.35 million Earth years ago, Mars had an eccentricity of roughly 0.002, much less than that of Earth today.[165] Mars's cycle of eccentricity is 96,000 Earth years compared to Earth's cycle of 100,000 years.[166] Mars has a much longer cycle of eccentricity with a period of 2.2 million Earth years, and this overshadows the 96,000-year cycle in the eccentricity graphs. For the last 35,000 years, the orbit of Mars has been getting slightly more eccentric because of the gravitational effects of the other planets. The closest distance between Earth and Mars will continue to mildly decrease for the next 25,000 years.[167]

Search for life[]

- Main article: Life on Mars

Viking 1 Lander's sampling arm created deep trenches, scooping up material for tests (Chryse Planitia).

The current understanding of planetary habitability—the ability of a world to develop environmental conditions favorable to the emergence of life—favors planets that have liquid water on their surface. Most often this requires the orbit of a planet to lie within the habitable zone, which for the Sun extends from just beyond Venus to about the semi-major axis of Mars.[168] During perihelion, Mars dips inside this region, but the planet's thin (low-pressure) atmosphere prevents liquid water from existing over large regions for extended periods. The past flow of liquid water demonstrates the planet's potential for habitability. Recent evidence has suggested that any water on the Martian surface may have been too salty and acidic to support regular terrestrial life.[169]

The lack of a magnetosphere and the extremely thin atmosphere of Mars are a challenge: the planet has little heat transfer across its surface, poor insulation against bombardment of the solar wind and insufficient atmospheric pressure to retain water in a liquid form (water instead sublimes to a gaseous state). Mars is nearly, or perhaps totally, geologically dead; the end of volcanic activity has apparently stopped the recycling of chemicals and minerals between the surface and interior of the planet.[170]

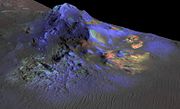

Detection of impact glass deposits (green spots) at Alga crater, a possible site for preserved ancient life[171]

Evidence suggests that the planet was once significantly more habitable than it is today, but whether living organisms ever existed there remains unknown. The Viking probes of the mid-1970s carried experiments designed to detect microorganisms in Martian soil at their respective landing sites and had positive results, including a temporary increase of CO2 production on exposure to water and nutrients. This sign of life was later disputed by scientists, resulting in a continuing debate, with NASA scientist Gilbert Levin asserting that Viking may have found life. A re-analysis of the Viking data, in light of modern knowledge of extremophile forms of life, has suggested that the Viking tests were not sophisticated enough to detect these forms of life. The tests could even have killed a (hypothetical) life form.[172] Tests conducted by the Phoenix Mars lander have shown that the soil has a alkaline pH and it contains magnesium, sodium, potassium and chloride.[173] The soil nutrients may be able to support life, but life would still have to be shielded from the intense ultraviolet light.[174] A recent analysis of martian meteorite EETA79001 found 0.6 ppm ClO4−, 1.4 ppm ClO3−, and 16 ppm NO3−, most likely of martian origin. The ClO3− suggests presence of other highly oxidizing oxychlorines such as ClO2− or ClO, produced both by UV oxidation of Cl and X-ray radiolysis of ClO4−. Thus only highly refractory and/or well-protected (sub-surface) organics or life forms are likely to survive.[175] A 2014 analysis of the Phoenix WCL showed that the Ca(ClO4)2 in the Phoenix soil has not interacted with liquid water of any form, perhaps for as long as 600 Myr. If it had, the highly soluble Ca(ClO4)2 in contact with liquid water would have formed only CaSO4. This suggests a severely arid environment, with minimal or no liquid water interaction.[176]

Scientists have proposed that carbonate globules found in meteorite ALH84001, which is thought to have originated from Mars, could be fossilized microbes extant on Mars when the meteorite was blasted from the Martian surface by a meteor strike some 15 million years ago. This proposal has been met with skepticism, and an exclusively inorganic origin for the shapes has been proposed.[177]

Small quantities of methane and formaldehyde detected by Mars orbiters are both claimed to be possible evidence for life, as these chemical compounds would quickly break down in the Martian atmosphere.[178][179] Alternatively, these compounds may instead be replenished by volcanic or other geological means, such as serpentinization.[138]

Impact glass, formed by the impact of meteors, which on Earth can preserve signs of life, has been found on the surface of the impact craters on Mars.[180][181] Likewise, the glass in impact craters on Mars could have preserved signs of life if life existed at the site.[182][183][184]

Habitability[]

The German Aerospace Center discovered that Earth lichens can survive in simulated Mars conditions, making the presence of life more plausible according to researcher Tilman Spohn.[185] The simulation based temperatures, atmospheric pressure, minerals, and light on data from Mars probes.[185] An instrument called REMS is designed to provide new clues about the signature of the Martian general circulation, microscale weather systems, local hydrological cycle, destructive potential of UV radiation, and subsurface habitability based on ground-atmosphere interaction.[186][187] It landed on Mars as part of Curiosity (MSL) in August 2012.

Exploration[]

- Main article: Exploration of Mars

Panorama of Gusev crater, where Spirit rover examined volcanic basalts

Recent Mars information comes from seven active probes on or in-orbit around Mars, including five orbiters and two rovers. This includes 2001 Mars Odyssey,[188] Mars Express, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, MAVEN, Mars Orbiter Mission, Opportunity, and Curiosity.

Dozens of crewless spacecraft, including orbiters, landers, and rovers, have been sent to Mars by the Soviet Union, the United States, Europe, and India to study the planet's surface, climate, and geology. The public can request images of Mars via the HiWish program.

The Mars Science Laboratory, named Curiosity, launched on November 26, 2011, and reached Mars on August 6, 2012 UTC. It is larger and more advanced than the Mars Exploration Rovers, with a movement rate up to 90 m (Template:Convert/round ft) per hour.[189] Experiments include a laser chemical sampler that can deduce the make-up of rocks at a distance of 7 m (Template:Convert/round ft).[190] On February 10, 2013, the Curiosity rover obtained the first deep rock samples ever taken from another planetary body, using its on-board drill.[191]

On September 24, 2014, Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), launched by the Indian Space Research Organisation, reached Mars orbit. ISRO launched MOM on November 5, 2013, with the aim of analyzing the Martian atmosphere and topography. The Mars Orbiter Mission used a Hohmann transfer orbit to escape Earth's gravitational influence and catapult into a nine-month-long voyage to Mars. The mission is the first successful Asian interplanetary mission.[192]

Future[]

- Main article: Exploration of Mars#Timeline of Mars exploration

Planned for March 2016 is the launch of the InSight lander, together with two identical CubeSats that will fly by Mars and provide landing telemetry. The lander and CubeSats are planned to arrive at Mars in September 2016.[193]

The European Space Agency, in collaboration with Roscosmos, will deploy the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter and Schiaparelli lander in 2016, and the ExoMars rover in 2018. NASA plans to launch its Mars 2020 astrobiology rover in 2020.

The United Arab Emirates' Mars Hope orbiter is planned for launch in 2020, reaching Mars orbit in 2021. The probe will make a global study of the Martian atmosphere.[194]

Several plans for a human mission to Mars have been proposed throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century, but no active plan has an arrival date sooner than 2025.

Astronomy on Mars[]

- Main article: Astronomy on Mars

Phobos transits the Sun (Opportunity; March 10, 2004)

Tracking sunspots from Mars

With the existence of various orbiters, landers, and rovers, it is possible to do astronomy from Mars. Although Mars's moon Phobos appears about one third the angular diameter of the full moon as it appears from Earth, Deimos appears more or less star-like and appears only slightly brighter than Venus does from Earth.[195]

There are various phenomena, well-known on Earth, that have been observed on Mars, such as meteors and auroras.[196] A transit of Earth as seen from Mars will occur on November 10, 2084.[197] There are transits of Mercury and transits of Venus, and the moons Phobos and Deimos are of sufficiently small angular diameter that their partial "eclipses" of the Sun are best considered transits (see Transit of Deimos from Mars).[198][199]

On October 19, 2014, Comet Siding Spring passed extremely close to Mars, so close that the coma may have enveloped Mars.[200][201][202][203][204][205]

Viewing[]

Animation of the apparent retrograde motion of Mars in 2003 as seen from Earth

Because the orbit of Mars is eccentric, its apparent magnitude at opposition from the Sun can range from −3.0 to −1.4. The minimum brightness is magnitude +1.6 when the planet is in conjunction with the Sun.[206] Mars usually appears distinctly yellow, orange, or red; the actual color of Mars is closer to butterscotch, and the redness seen is just dust in the planet's atmosphere. NASA's Spirit rover has taken pictures of a greenish-brown, mud-colored landscape with blue-grey rocks and patches of light red sand.[207] When farthest away from Earth, it is more than seven times as far from the latter as when it is closest. When least favorably positioned, it can be lost in the Sun's glare for months at a time. At its most favorable times—at 15- or 17-year intervals, and always between late July and late September—a lot of surface detail can be seen with a telescope. Especially noticeable, even at low magnification, are the polar ice caps.[208]

As Mars approaches opposition, it begins a period of retrograde motion, which means it will appear to move backwards in a looping motion with respect to the background stars. The duration of this retrograde motion lasts for about 72 days, and Mars reaches its peak luminosity in the middle of this motion.[209]

Closest approaches[]

Relative[]

The point at which Mars's geocentric longitude is 180° different from the Sun's is known as opposition, which is near the time of closest approach to Earth. The time of opposition can occur as much as 8.5 days away from the closest approach. The distance at close approach varies between about 54[210] and about 103 million km due to the planets' elliptical orbits, which causes comparable variation in angular size.[211] The last Mars opposition occurred on April 8, 2014 at a distance of about 93 million km.[212] The next Mars opposition occurs on May 22, 2016 at a distance of 76 million km.[212] The average time between the successive oppositions of Mars, its synodic period, is 780 days but the number of days between the dates of successive oppositions can range from 764 to 812.[213]

As Mars approaches opposition it begins a period of retrograde motion, which makes it appear to move backwards in a looping motion relative to the background stars. The duration of this retrograde motion is about 72 days.

Absolute, around the present time[]

Mars oppositions from 2003–2018, viewed from above the ecliptic with Earth centered

Mars made its closest approach to Earth and maximum apparent brightness in nearly 60,000 years, 55,758,006 km (Template:Convert/AU mi), magnitude −2.88, on August 27, 2003 at 9:51:13 UT. This occurred when Mars was one day from opposition and about three days from its perihelion, making it particularly easy to see from Earth. The last time it came so close is estimated to have been on September 12, 57 617 BC, the next time being in 2287.[214] This record approach was only slightly closer than other recent close approaches. For instance, the minimum distance on August 22, 1924 was Template:Val, and the minimum distance on August 24, 2208 will be Template:Val.[166]

Historical observations[]

- Main article: History of Mars observation

The history of observations of Mars is marked by the oppositions of Mars, when the planet is closest to Earth and hence is most easily visible, which occur every couple of years. Even more notable are the perihelic oppositions of Mars, which occur every 15 or 17 years and are distinguished because Mars is close to perihelion, making it even closer to Earth.

Ancient and medieval observations[]

The existence of Mars as a wandering object in the night sky was recorded by the ancient Egyptian astronomers and by 1534 BCE they were familiar with the retrograde motion of the planet.[215] By the period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the Babylonian astronomers were making regular records of the positions of the planets and systematic observations of their behavior. For Mars, they knew that the planet made 37 synodic periods, or 42 circuits of the zodiac, every 79 years. They invented arithmetic methods for making minor corrections to the predicted positions of the planets.[216][217]

In the fourth century BCE, Aristotle noted that Mars disappeared behind the Moon during an occultation, indicating the planet was farther away.[218] Ptolemy, a Greek living in Alexandria,[219] attempted to address the problem of the orbital motion of Mars. Ptolemy's model and his collective work on astronomy was presented in the multi-volume collection Almagest, which became the authoritative treatise on Western astronomy for the next fourteen centuries.[220] Literature from ancient China confirms that Mars was known by Chinese astronomers by no later than the fourth century BCE.[221] In the fifth century CE, the Indian astronomical text Surya Siddhanta estimated the diameter of Mars.[222] In the East Asian cultures, Mars is traditionally referred to as the "fire star" (火星), based on the Five elements.[223][224][225]

During the seventeenth century, Tycho Brahe measured the diurnal parallax of Mars that Johannes Kepler used to make a preliminary calculation of the relative distance to the planet.[226] When the telescope became available, the diurnal parallax of Mars was again measured in an effort to determine the Sun-Earth distance. This was first performed by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1672. The early parallax measurements were hampered by the quality of the instruments.[227] The only occultation of Mars by Venus observed was that of October 13, 1590, seen by Michael Maestlin at Heidelberg.[228] In 1610, Mars was viewed by Galileo Galilei, who was first to see it via telescope.[229] The first person to draw a map of Mars that displayed any terrain features was the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens.[230]

Martian "canals"[]

Template:Multiple image

- Main article: Martian canal

By the 19th century, the resolution of telescopes reached a level sufficient for surface features to be identified. A perihelic opposition of Mars occurred on September 5, 1877. In that year, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli used a 22 cm (Template:Convert/round in) telescope in Milan to help produce the first detailed map of Mars. These maps notably contained features he called canali, which were later shown to be an optical illusion. These canali were supposedly long, straight lines on the surface of Mars, to which he gave names of famous rivers on Earth. His term, which means "channels" or "grooves", was popularly mistranslated in English as "canals".[231][232]

Influenced by the observations, the orientalist Percival Lowell founded an observatory which had Template:Convert/and/AonSoff (Template:Convert/and/AonSoff) telescopes. The observatory was used for the exploration of Mars during the last good opportunity in 1894 and the following less favorable oppositions. He published several books on Mars and life on the planet, which had a great influence on the public.[233][234] The canali were independently found by other astronomers, like Henri Joseph Perrotin and Louis Thollon in Nice, using one of the largest telescopes of that time.[235][236]

The seasonal changes (consisting of the diminishing of the polar caps and the dark areas formed during Martian summer) in combination with the canals lead to speculation about life on Mars, and it was a long-held belief that Mars contained vast seas and vegetation. The telescope never reached the resolution required to give proof to any speculations. As bigger telescopes were used, fewer long, straight canali were observed. During an observation in 1909 by Flammarion with an 84 cm (Template:Convert/round in) telescope, irregular patterns were observed, but no canali were seen.[237]

Even in the 1960s articles were published on Martian biology, putting aside explanations other than life for the seasonal changes on Mars. Detailed scenarios for the metabolism and chemical cycles for a functional ecosystem have been published.[238]

Spacecraft visitation[]

- Main article: Exploration of Mars

Once spacecraft visited the planet during NASA's Mariner missions in the 1960s and 70s these concepts were radically broken. The results of the Viking life-detection experiments aided an intermission in which the hypothesis of a hostile, dead planet was generally accepted.[239]

Mariner 9 and Viking allowed better maps of Mars to be made using the data from these missions, and another major leap forward was the Mars Global Surveyor mission, launched in 1996 and operated until late 2006, that allowed complete, extremely detailed maps of the Martian topography, magnetic field and surface minerals to be obtained.[240] These maps are available online; for example, at Google Mars. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Express continued exploring with new instruments, and supporting lander missions. NASA provides two online tools: Mars Trek, which provides visualizations of the planet using data from 50 years of exploration, and Experience Curiosity, which simulates traveling on Mars in 3-D with Curiosity.[241]

In culture[]

- Main article: Mars in culture

Mars is named after the Roman god of war. In different cultures, Mars represents masculinity and youth. Its symbol, a circle with an arrow pointing out to the upper right, is used as a symbol for the male gender.

The many failures in Mars exploration probes resulted in a satirical counter-culture blaming the failures on an Earth-Mars "Bermuda Triangle", a "Mars Curse", or a "Great Galactic Ghoul" that feeds on Martian spacecraft.[242]

Intelligent "Martians"[]

- Main article: Mars in fiction

The fashionable idea that Mars was populated by intelligent Martians exploded in the late 19th century. Schiaparelli's "canali" observations combined with Percival Lowell's books on the subject put forward the standard notion of a planet that was a drying, cooling, dying world with ancient civilizations constructing irrigation works.[243]

An 1893 soap ad playing on the popular idea that Mars was populated

Many other observations and proclamations by notable personalities added to what has been termed "Mars Fever".[244] In 1899 while investigating atmospheric radio noise using his receivers in his Colorado Springs lab, inventor Nikola Tesla observed repetitive signals that he later surmised might have been radio communications coming from another planet, possibly Mars. In a 1901 interview Tesla said:

It was some time afterward when the thought flashed upon my mind that the disturbances I had observed might be due to an intelligent control. Although I could not decipher their meaning, it was impossible for me to think of them as having been entirely accidental. The feeling is constantly growing on me that I had been the first to hear the greeting of one planet to another.[245]

Tesla's theories gained support from Lord Kelvin who, while visiting the United States in 1902, was reported to have said that he thought Tesla had picked up Martian signals being sent to the United States.[246] Kelvin "emphatically" denied this report shortly before departing America: "What I really said was that the inhabitants of Mars, if there are any, were doubtless able to see New York, particularly the glare of the electricity."[247]

In a New York Times article in 1901, Edward Charles Pickering, director of the Harvard College Observatory, said that they had received a telegram from Lowell Observatory in Arizona that seemed to confirm that Mars was trying to communicate with Earth.[248]

Early in December 1900, we received from Lowell Observatory in Arizona a telegram that a shaft of light had been seen to project from Mars (the Lowell observatory makes a specialty of Mars) lasting seventy minutes. I wired these facts to Europe and sent out neostyle copies through this country. The observer there is a careful, reliable man and there is no reason to doubt that the light existed. It was given as from a well-known geographical point on Mars. That was all. Now the story has gone the world over. In Europe it is stated that I have been in communication with Mars, and all sorts of exaggerations have spring up. Whatever the light was, we have no means of knowing. Whether it had intelligence or not, no one can say. It is absolutely inexplicable.[248]

Pickering later proposed creating a set of mirrors in Texas, intended to signal Martians.[249]

In recent decades, the high-resolution mapping of the surface of Mars, culminating in Mars Global Surveyor, revealed no artifacts of habitation by "intelligent" life, but pseudoscientific speculation about intelligent life on Mars continues from commentators such as Richard C. Hoagland. Reminiscent of the canali controversy, these speculations are based on small scale features perceived in the spacecraft images, such as 'pyramids' and the 'Face on Mars'. Planetary astronomer Carl Sagan wrote:

Mars has become a kind of mythic arena onto which we have projected our Earthly hopes and fears.[232]

Martian tripod illustration from the 1906 French edition of The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells

The depiction of Mars in fiction has been stimulated by its dramatic red color and by nineteenth century scientific speculations that its surface conditions might support not just life but intelligent life.[250] Thus originated a large number of science fiction scenarios, among which is H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds, published in 1898, in which Martians seek to escape their dying planet by invading Earth.

Influential works included Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles, in which human explorers accidentally destroy a Martian civilization, Edgar Rice Burroughs' Barsoom series, C. S. Lewis' novel Out of the Silent Planet (1938),[251] and a number of Robert A. Heinlein stories before the mid-sixties.[252]

Jonathan Swift made reference to the moons of Mars, about 150 years before their actual discovery by Asaph Hall, detailing reasonably accurate descriptions of their orbits, in the 19th chapter of his novel Gulliver's Travels.[253]

A comic figure of an intelligent Martian, Marvin the Martian, appeared on television in 1948 as a character in the Looney Tunes animated cartoons of Warner Brothers, and has continued as part of popular culture to the present.[254] In the 1950s, TV shows such as I Love Lucy made light of the popular belief in life on Mars; for example, when Lucy and Ethel were hired to portray Martians landing on the top of the Empire State Building as a publicity stunt for an upcoming movie.

After the Mariner and Viking spacecraft had returned pictures of Mars as it really is, an apparently lifeless and canal-less world, these ideas about Mars had to be abandoned, and a vogue for accurate, realist depictions of human colonies on Mars developed, the best known of which may be Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars trilogy. Pseudo-scientific speculations about the Face on Mars and other enigmatic landmarks spotted by space probes have meant that ancient civilizations continue to be a popular theme in science fiction, especially in film.[255]

The theme of a Martian colony that fights for independence from Earth is a major plot element in the novels of Greg Bear as well as the movie Total Recall (based on a short story by Philip K. Dick) and the television series Babylon 5. Video games use this element, including Red Faction and the Zone of the Enders series. Mars (and its moons) were the setting for the popular Doom video game franchise and the later Martian Gothic.

Moons[]

- Main article: Moons of Mars

Template:Multiple image

Mars has two relatively small natural moons, Phobos (about 22 km (Template:Convert/round mi) in diameter) and Deimos (about 12 km (Template:Convert/round mi) in diameter), which orbit close to the planet. Asteroid capture is a long-favored theory, but their origin remains uncertain.[256] Both satellites were discovered in 1877 by Asaph Hall; they are named after the characters Phobos (panic/fear) and Deimos (terror/dread), who, in Greek mythology, accompanied their father Ares, god of war, into battle. Mars was the Roman counterpart of Ares.[257][258] In modern Greek, though, the planet retains its ancient name Ares (Aris: Άρης).[259]

From the surface of Mars, the motions of Phobos and Deimos appear different from that of the Moon. Phobos rises in the west, sets in the east, and rises again in just 11 hours. Deimos, being only just outside synchronous orbit – where the orbital period would match the planet's period of rotation – rises as expected in the east but slowly. Despite the 30-hour orbit of Deimos, 2.7 days elapse between its rise and set for an equatorial observer, as it slowly falls behind the rotation of Mars.[260]

Orbits of Phobos and Deimos (to scale)

Because the orbit of Phobos is below synchronous altitude, the tidal forces from the planet Mars are gradually lowering its orbit. In about 50 million years, it could either crash into Mars's surface or break up into a ring structure around the planet.[260]

The origin of the two moons is not well understood. Their low albedo and carbonaceous chondrite composition have been regarded as similar to asteroids, supporting the capture theory. The unstable orbit of Phobos would seem to point towards a relatively recent capture. But both have circular orbits, near the equator, which is unusual for captured objects and the required capture dynamics are complex. Accretion early in the history of Mars is plausible, but would not account for a composition resembling asteroids rather than Mars itself, if that is confirmed.

A third possibility is the involvement of a third body or a type of impact disruption.[261] More recent lines of evidence for Phobos having a highly porous interior,[262] and suggesting a composition containing mainly phyllosilicates and other minerals known from Mars,[263] point toward an origin of Phobos from material ejected by an impact on Mars that reaccreted in Martian orbit,[264] similar to the prevailing theory for the origin of Earth's moon. Although the VNIR spectra of the moons of Mars resemble those of outer-belt asteroids, the thermal infrared spectra of Phobos are reported to be inconsistent with chondrites of any class.[263]

Mars may have moons smaller than 50 to 100 metres (Template:Convert/round to Template:Convert/round ft) in diameter, and a dust ring is predicted between Phobos and Deimos.[7]

See also[]

- Colonization of Mars

- Composition of Mars

- Darian calendar

- Geodynamics of Mars

- Geology of Mars

- Extraterrestrial life

- Exploration of Mars

- List of artificial objects on Mars

- List of chasmata on Mars

- List of craters on Mars

- List of mountains on Mars

- List of quadrangles on Mars

- List of rocks on Mars

- List of valles on Mars

- Seasonal flows on warm Martian slopes

- Terraforming of Mars

- Water on Mars

Notes[]

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednasa_hematite - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednorthcratersn - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednorthcraterguard - ↑ Millis, John P.. "Mars Moon Mystery". About.com. http://space.about.com/od/mars/a/Mars-Moon-Mystery.htm.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Template:Cite conference

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmarswater - ↑ 9.0 9.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedspecials1 - ↑ 10.0 10.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjsg.utexas.edu - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedesa050221 - ↑ 12.0 12.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedspacecraft1 - ↑ Template:Cite press release

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNASA – NASA Spacecraft Data Suggest Water Flowing on Mars - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGuardian - ↑ Jarell, Elizabeth M (February 26, 2015). "Using Curiosity to Search for Life". Mars Daily. http://www.marsdaily.com/reports/Using_Curiosity_to_Search_for_Life_999.html. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ↑ "The Mars Exploration Rover Mission". NASA. November 2013. pp. 20. http://mars.nasa.gov/mer/home/resources/MERLithograph.pdf. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ↑ Wilks, Jeremy (May 21, 2015). "Mars mystery: ExoMars mission to finally resolve question of life on red planet". EuroNews. http://www.euronews.com/2015/05/21/mars-mystery-exomars-mission-to-finally-resolve-question-of-life-on-red-planet/. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ↑ Howell, Elizabeth (January 5, 2015). "Life on Mars? NASA's next rover aims to find out.". The Christian Science Monitor. http://www.csmonitor.com/Science/2015/0105/Life-on-Mars-NASA-s-next-rover-aims-to-find-out. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednssdc - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedusra - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedrust - ↑ 23.0 23.1 NASA – Mars in a Minute: Is Mars Really Red? (Transcript)

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNimmo 2005 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedicarus213_2_451 - ↑ 26.0 26.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjacque03 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedscience324_5928_736 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjgr107_E6 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsci300a - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsci300b - ↑ "Geologic Map of Mars – 2014". USGS. July 14, 2014. http://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/3292/. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmagnetosphere - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedplates - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedssr96_1_4_197 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedzharkov93 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedicarus165_1 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbarlow88 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsciam080627 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednyt080626 - ↑ "Mars: The Planet that Lost an Ocean's Worth of Water". http://www.eso.org/public/news/eso1509/. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjog91 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedssr_96_1_4 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedag44_4 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameddc080304 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbbc080627 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmarssalt - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjpl_soil - ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjpl_dust_devil - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedgpl29_23_41 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedoleb33_4_515 - ↑ "NASA – NASA Rover Finds Clues to Changes in Mars' Atmosphere". nasa.gov. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/msl/news/msl20121102.html.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedh - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjgr110 - ↑ 56.0 56.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedkostama - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsci299 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednasa070315 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbbc040124 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKerr2005 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJaeger2007 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedlucchita_rosanova - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednature434 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCraddockHoward2002 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsci288 - ↑ 66.0 66.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednasa061206 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbbc061206 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednasa061206b - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLewis2006 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMatsubara2011 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednasa040303 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednasa101001 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednasa - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednationalgeographic - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednationalgeographic1 - ↑ 76.0 76.1 Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (March 18, 2013). "Curiosity Mars Rover Sees Trend In Water Presence". NASA. http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/news/whatsnew/index.cfm?FuseAction=ShowNews&NewsID=1446. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (March 19, 2013). "Curiosity breaks rock to reveal dazzling white interior". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-21340279. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ↑ Staff (March 20, 2013). "Red planet coughs up a white rock, and scientists freak out". MSN. Archived from the original on March 23, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130323164757/http://now.msn.com/white-mars-rock-called-tintina-found-by-curiosity-rover. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ↑ "NASA News Conference: Evidence of Liquid Water on Today’s Mars". NASA. September 28, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bDv4FRHI3J8&ab_channel=NASA.govVideo. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ↑ "NASA Confirms Evidence That Liquid Water Flows on Today’s Mars". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-confirms-evidence-that-liquid-water-flows-on-today-s-mars. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Drake, Nadia; 28, National Geographic PUBLISHED September. "NASA Finds 'Definitive' Liquid Water on Mars". http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/09/150928-mars-liquid-water-confirmed-surface-streaks-space-astronomy/. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ↑ Moskowitz, Clara. "Water Flows on Mars Today, NASA Announces". http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/water-flows-on-mars-today-nasa-announces/. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHead1999 - ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedicarus169 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedclouds - ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmira - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbrown - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedphillips - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsci315 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedOnset and migration of spiral troughs on Mars revealed by orbital radar - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMystery Spirals on Mars Finally Explained - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named2006-100 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKieffer2000 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPortyankina - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHugh2006 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsheehan_ch04 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedusgs - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedviking_1950_2000 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedseds_huygens - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedarchinal_caplinger - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNASAMola2007 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpers66 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedlunine99 - ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ "Online Atlas of Mars". Ralphaeschliman.com. http://ralphaeschliman.com/id30.htm. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ↑ Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (May 22, 2014). "NASA Mars Weathercam Helps Find Big New Crater". NASA. http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2014-162. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedwright03 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameducar_geography - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedemp9 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedemp45 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedscsdes49 - ↑ "Olympus Mons". mountainprofessor.com. http://www.mountainprofessor.com/olympus-mons.html.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedglenday09 - ↑ Wolpert, Stuart (August 9, 2012). "UCLA scientist discovers plate tectonics on Mars". UCLA. http://newsroom.ucla.edu/portal/ucla/ucla-scientist-discovers-plate-237303.aspx. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedcushing_titus_wynn07 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednau070328 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbbc070317 - ↑ Jones, Nancy; Steigerwald, Bill; Brown, Dwayne; Webster, Guy (October 14, 2014). "NASA Mission Provides Its First Look at Martian Upper Atmosphere". NASA. http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2014-351. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedswind - ↑ "Multiple Asteroid Strikes May Have Killed Mars's Magnetic Field". WIRED. January 20, 2011. http://www.wired.com/2011/01/mars-dynamo-death/.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedswind2 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbolonkin09 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedatkinson07 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedcarr06 - ↑ "Abundance and Isotopic Composition of Gases in the Martian Atmosphere from the Curiosity Rover". Sciencemag.org. July 19, 2013. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/341/6143/263.abstract. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameddusty - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmethane-me - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmethane - ↑ 134.0 134.1 134.2 134.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedplumes - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedhand08 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedresults - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednature460 - ↑ 138.0 138.1 Cite error: Invalid